By: Ahmed Saeed

PART 1

It was fifteen past seven in the evening but courtroom no.2 of the special banking court, Lahore was brimming with people. It was October 1st and the year 2014. The day wasn’t very hot, but the room was getting a little suffocating due to over congestion.

For many others in the room, it was like any other day, but for Tariq Mahmood Malik and Shahid Rasool Dar, it could well be the most important day of their lives. It was important for them because their cases, which were initiated in 1992 were going to be adjudicated after 22 years.

The verdict was scheduled to be announced at 11am, but got postponed as the judge hadn’t been able to write down the complete judgment. So, he said that he would announce it in the evening, after the official timings.

The accused had been charged with fraud and misuse of authority by the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA)) under the sections of Pakistan Penal Code (PPC).

Malik and Dar were sitting in the second row as the first row had been taken over by their lawyers, who were wearing their traditional black suits. Their counsels seemed composed as they chit-chatted about the upcoming elections of the Lahore Bar Association.

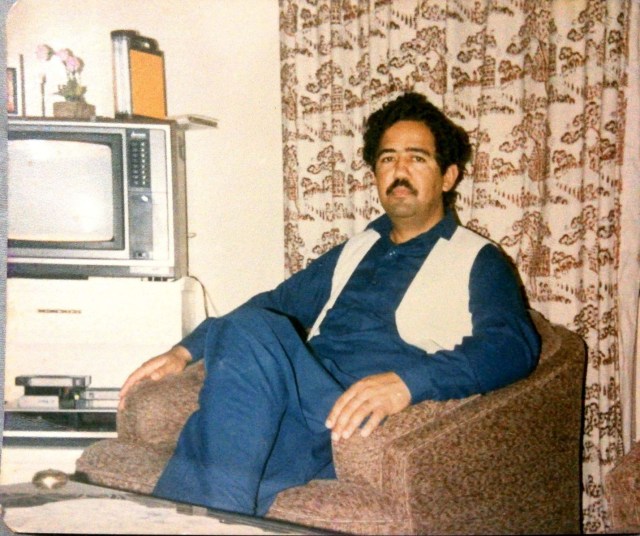

Sitting behind his lawyer, Malik, in his early-sixties had mixed thoughts racing through his mind. He was happy because finally his trial was going to be concluded but worried about what would happen if he got convicted and sentenced to prison. He did not want to think about it any further as the thought of leaving his wife and children was making him restless.

To get over it, he gazed at his wristwatch and cleared the sweat drops from his forehead with the handkerchief.

This was the fourth time that Malik was going through this phase, as the judge had postponed the verdict three times before without citing any reason. But this time, he wanted an end to the ordeal, which had gone on for more than two decades.

Suddenly, the door of the judge’s chamber opened with a creaky sound and a middle-aged man, carrying a pack of files in his hand appeared. This was the signal that the judge was arriving soon and proceedings were going to start.

Soon after, the judge wearing the traditional black gown came out of his chamber. Everyone in the room stood up as a mark of respect for the court. The judge, after settling down on his chair, cast a glance over the courtroom and asked everyone to take their seats.

After taking some papers from his clerical staff, the judge put on his glasses. He read the papers for a few seconds and ordered for silence in the room in a little loud tone. He then started reading out the verdict of the 22-year-old case.

According to the verdict, Tariq Mahmood Malik had been proven guilty and was sentenced for seven years rigorous imprisonment with a fine of Rs 0.3 million. The sentence was given under section 409 of Pakistan Penal Code (PPC). However, Judge exonerated the co-accused, Shahid Rasool Dar by extending the benefit of the doubt to him.

After announcing the verdict, the judge rose up and left the courtroom immediately.

Malik was stunned as the mere thought of spending the next seven years in jail was incomprehensible for him. But what made him more astonished was the fact that he was sentenced under section 409 of PPC, a clause which was neither mentioned in the First Information Report (FIR) not which he was charged for.

Malik tried to discuss this with his lawyer but the police didn’t allow him to talk, led him out of the courtroom and pushed him to the prisoners’ van, to be transported to Kot Lakhpat Jail.

It was the end of the trial for Malik as well as the start of tribulations for him. He knew he still had to fight another long legal battle to clear the stigma of being convicted under charges of fraud.

The Case:

It was the year 1992 when, after torrential rains, heavy flooding occurred in the northern regions of Pakistan. District Jhelum, situated on the bank of Neelum River was severely affected by the natural calamity. Flood water entered the city, claiming scores of lives and causing damages to business and property worth millions of rupees.

Many of the small businessmen in Jhelum City lost all their earnings and assets in the flood and were looking toward the government to help them in restarting their ventures once again.

To compensate their loss, the government decided to reimburse 0.3 million to every shopkeeper, whose shop was destroyed by the flood. A committee under the chairmanship of a local politician was formed. Officials of local administration and representatives of traders’ unions were members of the said committee.

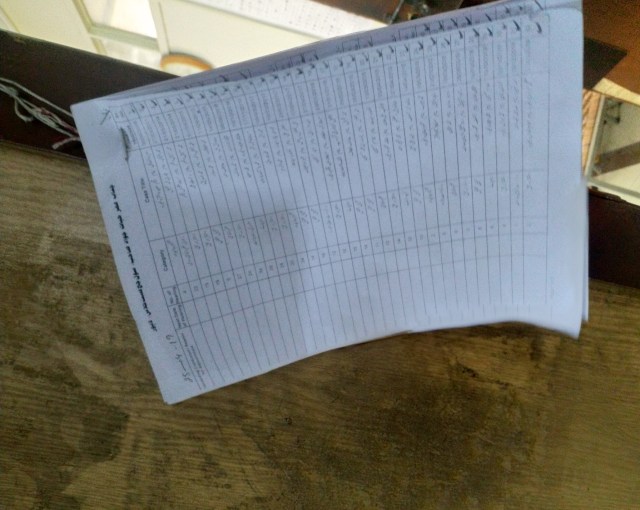

The committee was responsible to authenticate every application and then made a final list of the affectees. The list would be sent to Small Business Finance Cooperation (SBFC), a government organization established to help small traders, which had to issue cheques to the affected businessman.

Traders had the option to deposit the cheque at any bank if they already had an account.

Tariq Mahmood Malik was serving as branch manager of United Bank Limited when one day, a man named Muhammad Taimur came and requested him to open a bank account. He had the cheque of Muslim Commercial bank issued by SBFC. He also had all the relevant documents, verified by government agencies, required to open an account.

Malik verified his credentials and opened his account with the cheque of Rs 0.3 million. As the cheque belonged to MCB, Malik sent the cheque for verification and upon clearance, Taimur’s account was credited with the amount.

After three days, Taimur came and withdrew all the money from his account. It was a normal transaction – something Malik could never have dreamt would change the course of his life.

A year later in 1993, Malik received a show-cause notice from the FIA that an investigation regarding financial embezzlement had been initiated against him. On asking for more details, Malik was told that he opened an account of Mr. Muhamamd Taimur, who got the cheque from SBFC by deceit, disguising himself as a flood affectee.

Since Taimur deposited the cheque and subsequently cashed it from Malik’s branch, the FIA accused both of them for financial embezzlement which caused damaged to the national exchequer.

Malik told the FIA that if Taimur had obtained the cheque through fraudulent means, then the FIA should ask the scrutiny committee and not him. He opened the account because he had all the necessary documents which were also duly authenticated by the competent authorities.

Rejecting his explanation, the FIA registered a case against him under charges of fraud and forgery in 1994

After being booked in an FIR, Malik went to banking court Lahore and sought bail before arrest. Court ordered him to fully cooperate with the agency in the investigation. Malik appeared before the FIA and gave proof of his innocence and told them he was neither guilty nor a beneficiary of the fraud in any way.

In April 1995, the banking court approved his bail and asked FIA to formally commence the trial.

The Trial:

After being investigated for more than one and a half years, the FIA formally completed the challan against him and charged him under four sections, 109, 420, 468 and 471 of PPC. Sections 420, 468 and 471 were related to the fraud and making forged documents while 109 dealt with abetment in a crime.

As the trial started in late 1995, Malik requested the court to shift his case from Lahore to banking court in Rawalpindi because going to Lahore after every week or fortnight was affecting his professional duties.

The banking court accepted his request and the trial was shifted to Rawalpindi, but after two or three hearings, the case was again shifted to Lahore.

In 1997, the case picked up pace as new evidence came to light through the FIA. After a few other hearings, the court was about to adjudicate the case but it was then adjourned for the indefinite time period. The adjournment went on without any signs of recommencement anytime soon. Malik was getting mentally disturbed with every passing day. He wanted to get rid of the case so he wrote repeated applications to the banking court, asking it to adjudicate his case at the earliest.

“I was very worried during all these years. The case has disturbed my professional as well as my personal life,” said Malik adding, “My reputation was at stake and I wanted to clear my name as soon as possible, so I wrote to the court to hear my case on a priority basis”.

Heeding Malik’s repeated requests, the court decided to give him an “early hearing.”

After a hiatus of six years, the court restarted the trial in 2003 and summoned all parties once again. Since a long time had passed, the court asked both the parties to start the trial from scratch.

The trial started but was moving forward at a snail’s pace. There was a hearing after every two or three months. During these hearings, members of the scrutiny committee and the SBFC’s official testified in the favor of Malik and told the court that he was not the beneficiary of the fraudulent act committed by Taimur.

Meanwhile, the judges kept on changing after every three months. Every new judge took his time to understand the background of the case.

“Our case was pretty strong and one the judge remarked in our favor and I was hopeful that the judge would quash the case in the next hearing,” said Malik. “But the next time, I found a new judge sitting, who was oblivious of the previous hearing’s development”.

Time flew by and in 2007, lawyers started a movement against the removal of the Chief Justice of Pakistan. The movement lasted two years and during this time strikes became a new normal, choking the already overburdened judicial apparatus.

Malik and his case both grew older. He ultimately retired from United bank in 2008, but his case was still nowhere close to ending.

Judgment:

After retirement, Malik moved to Rawalpindi to provide quality education to his four children. Time flew and on 25th September, 2014, he got a call from his lawyer who told him that the banking court was going to announce the decision of his case of October 1st. The lawyer advised him to ensure his presence in the courtroom at the time of verdict being announced.

This was not the first time that the court had fixed the case for final adjudication; the same had happened three times before but the court was adjourned without announcing the ruling.

As the case had taken so long, Malik’s family had forgotten about it. But when Malik was summoned to Lahore, he told his eldest son, Muhammad Awais, to not lose hope if he was imprisoned and to look after the family in his absence.

Malik went to Lahore to hear the verdict of the case which he had been pursuing for the last two decades and spent a significant amount of his earnings on.

The judge found him guilty and convicted him under section 409 which deals with criminal breach of trust by public servant, or by banker, merchant or agent of PPC. He was sentenced to seven years in jail and imposed a fine of Rs 0.3 million.

The judgment was shocking for Malik and his lawyer as the court convicted him under a section which was neither mentioned in the FIR nor was he indicted for it.

Malik knew that he was wrongfully convicted but he would have to fight another legal battle to prove his innocence.

“I knew legal avenues are there for me to challenge this ruling but I didn’t know how many more years of my life would be wasted in clearing my name. At that point I didn’t want to come out of jail without being pronounced a clean man by the courts,” Malik explained his feelings after being sent to jail.

Post-conviction Life :

As Malik was sentenced by a court in Lahore, he was shifted to Kot Lakhpat Jail. This just added to his hardships because his entire family was settled in Rawalpindi and it was impossible for them to visit him every week.

Due to old age, he had become a patient of high blood pressure and diabetes and needed proper medical care to remain fit. He then appealed to jail authorities to shift him to Adiyala Jail Rawalpindi so that his family could meet regularly.

Jail officials accepted his application after two years and shifted him to Rawalpindi.

In the meantime, he filed an appeal in the Lahore High Court (LHC), against the trial court’s judgment, highlighting glaring errors in it. His appeal after initial hearings was deferred for an indefinite time.

He then filed a bail application on health grounds in the Lahore High Court which was dismissed in the first hearing.

He then moved to Supreme Court for granting bail on statutory grounds. The Supreme also dismissed his plea but observed that prima facially, the appellant had strong grounds against the trial court’s verdict. Supreme Court in its written order also asked the LHC to adjudicate his petition at the earliest.

Appeal:

Despite the apex court’s clear instructions, Malik’s appeal against conviction couldn’t get an early hearing in the high court. He thought he would get quick relief from the high court as the situation wouldn’t be worse as it used to be in lower courts.

Contrary to his belief, Malik faced a similar situation in the high court too. The plea took a year to be placed for hearing before the divisional bench. On the first hearing, the high court issued notices to FIA and adjourned the case for three months. On the next hearing, the two-member bench had been dissolved because one of the judges was transferred.

The case was sent back to the Chief Justice who referred it to another divisional bench. This took another four months but the appeal adjourned unheard because one member of the bench was out of the country to perform Umrah.

This kept happening for a long time. Either there was a strike call by the lawyers or the judge was on leave. The case kept transferring from one bench to another but it didn’t move an inch forward from the preliminary hearings.

In the meanwhile, Malik was languishing in jail. His health condition was continuously deteriorating due to poor hygiene and food. His family asked him to write a mercy petition to the President, as he had completed one-third of the jail term and the remaining sentence would be slashed if the President gave him a pardon.

But for Malik, getting out of jail was a secondary thing; his main objective was to get his name cleared. He was quite optimistic that the high court would exonerate him from all the charges respectfully.

“I knew I was innocent and the trial court verdict would be set aside by the high court one day, I was just waiting for that lucky day,” Malik said.

That lucky day came on 7 May 2018. Three years, seven months and seven days after he got convicted from the banking court.

Exoneration:

After remained pending in the high court for over three years, Malik’s appeal got fixed before the divisional bench on 7th May. Luckily, that day, judges, the prosecutor, and lawyers were all present in the court.

The court, after ascertaining the facts of the case and reviewing the trial court’s judgment, observed that it didn’t find anything against the appellant and the case should not have been registered against him in the first place.

The court also showed its bewilderment on the banking court’s verdict. The bench was surprised to know that Malik was convicted under a section of PPC that was neither mentioned in the FIR nor he was indicted for it by the court.

Besides, the bench also highlighted many other glaring errors floating on the surface of the trial court’s ruling.

The court also noted that there had been an inordinate delay in adjudicating such an open and shut case and such long delay in dispensing justice was equivalent to denying justice.

In the end, the court in its written order set aside the trial court’s verdict and acquitted Malik from all charges, ordering his immediate release from the jail.

A free man:

After completing the official requirements, Malik was released from the Adyala Jail on 19 May 2018

He stepped out of the jail, leaving behind all the hardships and accusation. He was now a free man and a clean man as well. A new life with his loves ones was waiting for him.

Although Malik has some regrets about wasting the most beautiful years of his life in jail after being wrongfully convicted, he still doesn’t blame any individual for his sufferings.

“It was the system that made the false case, lingered it on for years and then wrongfully convicted me,” said Malik as he explained his takeaway from the journey to justice. “I am not the only one who has to go through all this, believe me, jails are full of such cases. This would only stop if we rectify all the loopholes that exist in our criminal justice system”.

Part 2

With 1.9 million cases pending in courts, delayed justice has become an issue of public importance in Pakistan. Before the general elections of 2018, three major political parties – the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz, Pakistan Peoples Party and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf – in their manifestos promised to provide expeditious and inexpensive justice if they were voted to power.

According to research carried out by the Supreme Court of Pakistan in 2015, a single case takes a whopping 25 years on average from registration to be finally adjudicated by the Apex Court. In some scenarios, this time period can last as long as four or five decades.

The problem of inordinate delays in the dispensation of justice involves multiple stakeholders of the criminal justice apparatus of the country. It would therefore need a holistic and comprehensive approach and coordination from all the key players to resolve the issues.

Although many government departments, including but not limited to police and prosecution, are to be blamed for the delays, the bar and bench being the two main components of the judicial process are the most to blame for the malfunctioning of the system.

Both stemming from the same fraternity, judges and lawyers accuse each other as the main culprits for blocking the system either due to incompetence or because of vested interests.

The lawyers’ community is of the view that incompetence and corruption of the judges slows down the dispensation of justice. On the other hand, the bench blames the lawyers for choking the system with their routine strikes, pressurizing judges for long adjournments and filing frivolous petitions.

The responsibility to provide expeditious and inexpensive justice falls on the system. However, the ultimate cost is being paid by the genuine litigant, who knocks the doors of the court in the hope to get speedy justice as promised in Article 37(d) of the Constitution of Pakistan.

The delays not only cause heavy financial loss to the litigants but, in some instances, people have to spend many years in jail without being proven guilty due to unnecessary postponements.

Long Adjournments: Blessing or a Curse?

Asad Gillani, a young lawyer based in Islamabad believes loopholes in the system suit everyone. He said that lawyers asked for long delays at the behest of their clients as in some cases, lawyers are forced to put the case in hibernation for as long as possible.

“Not all litigants want their cases to be adjudicated swiftly. Rather, in some cases, lawyers are strictly asked by their clients to take long adjournments as it suits them,” Gillani said adding. “But I still think judges are to be blamed for the delays because they allow the adjournments.”

He was of the view that judges of district courts usually succumb to the pressure of lawyers and grant long postponements. He termed the trial court as the weakest link in the criminal justice process because the judges there do not have enough powers that are vital to smoothly conduct a trial.

“Over the years, superior courts have made trial courts toothless by snatching their powers granted in law causing unnecessary delays,” he said.

For example, the law empowers the magistrate to seize the right of response from a defendant if they don’t submit it in 30 days. But the Supreme Court has weakened this law through its interpretation.

“Trial courts are basic units of the system but have been systemically weakened in the past and now they are unable to perform their duties without any fear or favor,” said Gillani.

To overcome the issue of delayed justice, Gillani filed public interest litigation in the Supreme Court under Article 184/3 of the Constitution, praying to amend the country’s laws to empower courts so that they can fight the menace of postponements.

In the petition, all registrars of high courts, the Federal Government, Provincial Governments and Law and Justice Commission Pakistan were made respondents. The Supreme Court rejected the petition but the former Chief Justice, Saqib Nisar, took some steps to overhaul the country’s delay-ridden judicial system.

Strikes: A New Normal

After the successful lawyers’ movement of 2007, bar councils and associations have emerged as a pressure group. To coerce the courts and governments to fulfill their demands, these bodies often use strikes as the trump card. In some instances, the strike continues for months where no lawyer is allowed to present before any judge.

This phenomenon of regular strikes has become the biggest obstacle in the smooth running of the system and has resulted in multiplying the woes of the litigants.

Raheel Kamran Sheikh, a senior member of the Pakistan Bar Council (PBC) which is the apex body of lawyers in the country admits that since 2007, strikes called by lawyers’ bodies have damaged the justice system in the country.

“I am personally against these strikes and during my tenure in PBC, we never announced any strike except the one day of grief we observed after the Quetta carnage in 2016,” he said.

He further said that the PBC does not condone or support any type of strikes being called by provincial or district bar associations. The PBC has not, however, taken any corrective measures in this regard.

“Yes, we have failed there and the PBC should play its supervisory role to bar them from going on strikes over petty issues,” Sheikh added.

Gillani also thinks that unnecessary and protracted strikes have severely affected the capacity of the system to complete the trial in minimum possible time.

“A one-day strike means that nearly 300 cases would be postponed for the next hearing, so it just increases the number of cases in daily cause lists, forcing the judge to give long adjournments to the cases,” said Gillani, explaining how a single day’s strike affects the working of the court.

“If a single day strike can delay the hearing of average 300 cases, then you can calculate how many cases would be delayed by a week-long strike.”

Although not all the lawyers want to observe strikes and boycott court proceedings, they are compelled to do so because of peer pressure.

“In some cases, we really want to go on strikes as we deem it necessary, but in most instances, I have to boycott the courts just because my fellow lawyers want me to do so,” Gillani said.

Judicial Activism:

Since 2007, Pakistan has witnessed two waves of judicial activism. One in the tenure of former Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhary and the other during retired justice Saqib Nisar’s stint as top judge. The Supreme Court played an active role in deciding matters of public importance by extensively using its suo-motu powers. However, during all these years, the backlog of pending cases in the lower courts and especially in the apex court has increased many folds.

During the tenure of Saqib Nisar as Chief Justice of Pakistan, the number of cases pending in the apex court has gone up from 32,000 to almost 40,000.

Journalist Hasnaat Malik, who has been covering the Supreme Court for more than a decade, believes the increase in pendency can be attributed to two main factors. First, during judicial activism, people looked towards the apex court to get relief in every matter; a large number of public interest litigations were filed that resulted in the increase of pendency of under-trial cases.

The second aspect is the excessive use of suo-motu powers by the Supreme Court. Saqib Nisar has taken numerous suo-motu notices; as a result, he gave little time to the cases which came through appeals or petitions from subordinate courts for final adjudication.

“Many of the suo-motu notices the Supreme Court had taken were directly related to the executive branch of the state,” said Malik. “So, the priority of the top judge shifted to high profile cases which made highlights in the media but the ordinary litigant suffered a lot.”

However, PBC deems suo motu powers necessary for the enforcement of fundamental rights of the public promised by the Constitution.

Raheel Kamran Sheikh is of the view that even the excessive use of Article 184/3 by the apex court does not choke the system.

“Suo-motu jurisdiction empowers the court to safeguard the rights of marginalized groups by giving them direct relief,” said Sheikh, adding, “Definitely the filing in Supreme Court increases during judicial activism as people see hope of getting justice against the state institutions but it does not have any adverse impact on the regular cases.”

Nevertheless, Sheikh stressed that while using suo-motu powers, the Supreme Court must ensure the principle of fairness and due procedure of law. It should not be done by compromising the standards of justice.

Frivolous petitions:

Registration of false cases and filing frivolous petitions is used as a tool to pressurize the opponent. In rural societies, this trend has turned into a menace. People move the court against their rival either preemptively or reactively. In both scenarios, the appellant does not really want the court to act on the application; rather they just want to use the case as leverage to have an upper hand if there is an out of court settlement.

Such facetious litigations are not only creating an unnecessary blockage in the system but also jeopardizing the standards of justice in the country.

Besides wasting the precious time of the court, such non-serious lawsuits are also compromising the evolution of case law jurisprudence, which is the back-bone in common law system.

Although section 182 of PPC empowers the courts to impose a fine or imprison any person who deliberately files a wrong case, in most instances, judges exercise the policy of judicial restraint and avoid penalizing anyone for filing a frivolous case.

Wasif Jamil, who practices law in Civil Courts Lahore, said that almost half of the civil petitions filed in the country are either partially fallacious or entirely false, yet the courts have to hear all of them at least for one time.

“Even to dismiss a petition at the preliminary stage, a judge has to hear it before rejecting it,” said Jamil. “If half of the cases listed for trial in a day are meaningless, then they will have a very negative effect on the progress of other cases.”

To overcome the issue of false litigation, Jamil suggested that the government should appoint law officers in district and session courts, who scrutinize every case and only list those cases for hearings which have some legal substance and touch the minimum threshold of being heard by the judge.

“To discourage this trend of false litigation, we should nip the evil in the bud by kicking out false cases in the scrutiny stage,” said Jamil.

JUDGES’ INCOMETENCE & ACCOUNTABILITY:

As Pakistan is a common law country, it has an adversarial legal system. Under this system, the parties to a case are usually represented by attorneys who actively present the concerned party’s case. The contest is before an impartial person or group of people, usually a jury or judge.

Since the entire criminal justice system revolves around the judges, the number of judges and their competence directly affect the progress and settlement of the cases.

Long adjournments and delays in the adjudication of cases have a direct correlation with the dearth of judges. Across Pakistan, there are almost 3,000 adjudicators including magistrates, session judges, special court judges and members of the superior judiciary.

Lawyers believe that shortage of judges is another major reason for the sorry state of affairs in the courts. In the lower courts, the situation is even more pitiful as judges are heavily overburdened.

Umar Gillani said that due to sheer burden of the workload, judges get exhausted and their fatigue reflects in the form of poor quality and delayed justice.

“On average, a civil judge has to hear 100 plus cases every day, which is humanly impossible,” Gillani said. “So, either he adjourns a large number of cases or listens to them half-heartedly without paying much attention to their merits.”

He pointed out many factors including low salary scale, no job security and slow career growth due to which competent lawyers avoid to become civil or session judges.

“Every lawyer wants to get elevated directly to the bench at the high court instead of inducting as a judge in the lower judiciary,” he said. “The government should increase the salary of lower courts’ judges and elevate more judges from the district judiciary to the higher courts.”

Addressing the issue, Raheel Kamran Sheikh said there is no mechanism for accountability of the incompetence of judges as they are appointed and promoted on the basis of personal liking.

He further said that until and unless we start rewarding and penalizing judges on the basis of their professional competence instead of pressures and vested interests, the problem of delayed justice will never be solved.

“Judges will only start performing better if they know that they can be removed from the post if they continuously pass erroneous judgments or have very slow pace of adjudicating cases,” Sheikh said, adding, “With such kind of accountability, not only incompetent judges will be washed out from the system, but the finest jurisprudence will be developed within a few years.”

According to Article 209 of the constitution, there is a Supreme Judicial Council which deals with the accountability of members of the superior judiciary, but since 1970, the forum has only ousted two judges from the bench and that too mainly on discipline charges.

Article-X of the Judges’ Code of Conduct says that a judge should make every effort to minimize the suffering of litigants by deciding cases expeditiously through proper, written judgments.

However, the council had never issued a show-cause notice to any judge over the violation of Article-X.

As far as accountability is concerned, the chief justice of the respective provincial high court is empowered to expel lower court’s judges if they have conduct unbecoming of a judge. But there is no institutionalized system of scrutiny of judges and chief justice often use their powers arbitrarily

Judge’s view on the delayed justice:

Former Chief Justice of Pakistan, Justice Jawad S. Khawaja, believes delays in the judicial system become inescapable because of the way common law system is set-up.

He said that the justice system has become stagnant simply because the laws have not evolved with time.

“Our code of criminal procedure is of 1898 and our civil laws are of 1908,” said Khawaja. “They are more than a century old. How can a judicial system function properly with outdated laws?”

Another prevailing issue is of the contrary languages on which the system is based, and in which the proceeding are held. Pakistan’s entire judicial system is set-up in English whereas the proceedings in the courtroom are held in Urdu. Khawaja believes that this issue leads to a lot of misinterpretation of judgments and can cause gross miscarriage of justice.

“When I was a high court judge, we saw cases which had a different meaning altogether once they were translated,” said Khawaja. “Because of that, we had to declare many trial court decisions null and void.”

Keeping this daunting problem in mind, Khawaja after becoming the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 2015, passed a landmark decision and directed federal and provincial governments to adopt Urdu as an official language in the country.

“As the head of Judiciary, I also ordered to change the language of the entire judicial system to Urdu, as a result of which court proceedings become smoother and judges started adjudging cases quicker,” Khawaja said.

There are a lot of provisions in the Constitution of Pakistan to make sure that the judicial system remains a strong pillar to which its people lean on in the time of need and get benefit from it. Article 37(d) of the Constitution says that justice should be quick and inexpensive for the people of the country. However, Khawaja is of another point of view.

“Justice can either be quick or inexpensive,” said Khawaja. “It cannot be both at the same time as it is a utopian thought for this country where people have only have vested interests. They only think about what they can take and not what they give back to the country. Since the birth of this nation people have only taken.”

Evolution in any field is necessary for its survival. If it is not evolving, it will not survive. When a long train of error shows invariably the same results, it is the duty and responsibility of those in power to change the system and bring in one which will provide judicial security to the people of the country.

“The legislative branch of the state has to amend the outdated laws and embed new technology,” said Khawaja. “Till the time it is not done, the hands of the judiciary will remain tied and it will not be able to function as quickly as the people of this country deserve.”

Part 3:

Way Forward:

The rising numbers of pendency and long duration to decide cases have put the entire system on high alert. People who are at the helm of the judicial affairs have realized that some bold and revolutionary steps have to be taken to rectify the shortcomings and errors prevailing in the system otherwise the whole structure would become dysfunctional.

The Supreme Court of Pakistan is taking a number of steps to clear the backlog of cases and accelerate the process to ensure the delivery of justice in the minimum possible time.

The current Chief Justice of the apex court, Asif Saeed Khosa, has vowed to avail every moment of his tenure to take corrective measures that contribute towards the quick resolution of cases at all levels of the judicial hierarchy.

He assured the nation that he would bring reforms in the judiciary to restore the faith of the public in the criminal justice system.

“I would also like to build some dams, a dam against undue and unnecessary delays in judicial determination of cases, a dam against frivolous litigation and a dam against fake witnesses and false testimonies and would also try to retire a debt, the debt of pending cases which must be decided at the earliest possible,” said Justice Khosa, while explaining his priorities as Chief Justice at the full court reference.

He has chalked out a multi-dimensional reforms agenda to put the system back on track. Besides establishing model courts, his strategy involves the use of technology to avoid delays and to pass over some matters to the executive from the judiciary’s domain to lessen the burden on judges and courts.

Model Courts:

To provide quick relief to the litigants and unclog the arteries of the judicial system, Chief Justice Khosa has ordered the establishment of model courts all across Pakistan as a pilot project.

They have started working from April 1st, 2019.

Special training was given to judges before appointing them in the model courts, where priority to old cases in given.

In the first 20 days of their establishment, model courts issued verdicts in 756 murder cases and 1,110 narcotics cases. Moreover, a total of 7,256 witnesses recorded statements before these courts.

Of all the cases decided by courts, 709 cases were pending for more than twenty years.

Despite this outstanding performance, lawyers termed the model courts illegal and extra-constitutional step and announced to protest.

Umar Gillani considers that model courts have been set up without any proper homework and in the long run, these courts will become part of the problem instead of the solution.

“Model courts system has two main problems, first there is an arbitrariness in it and secondly it will jeopardize the right of a fair trial as promised in Article 10-A of the constitution,” he said.

He was also skeptical about the number of cases being adjudged in such a short time period.

“If judges are deciding 100 cases per day on average, it is more than worrisome,” he said. “It means they are compromising on some procedural requirements and hastily announcing verdicts just to appease the higher authorities, but do remember that justice in haste is justice in waste.”

Discouragement of adjournments/ Frivolous Petitions

Since taking the oath, Justice Khosa has waged a war against unnecessary and long adjournments. He has also instructed the judges in the lower courts to not postpone cases without any valid reason.

Supreme Court has disposed of all the criminal appeals’ backlog and from May 2019 all the appeals will be directly put before the bench for hearing and final adjudication.

To discourage the trend of false litigation, the Supreme Court has started penalizing such applicants. Due to strict scrutiny of the applications and fear of being fined, the number of new petitions has fallen.

Kamran Sheikh has lauded the apex court’s approach of zero tolerance towards false litigations and he was optimistic that it will help the court focus on deserving cases.

“After becoming the top judge, Justice Khosa came down hard on false litigants, as a result of which people with real grievances are only approaching the court now,” said Sheikh. “Moreover, he has also discouraged politically motivated cases, which in the past have consumed a lot of court’s time and dragged it in he controversies.”

USE OF NEW TECHNOLOGY

Outdated laws and old techniques have also contributed to clogging the justice system. The effective use of modern practices and information technology is necessary to maximize efficiency and save time.

The use of the Case Flow Management System (CFMS) by Lahore High Court has brought a visible change. It not only fast-tracks the clerical procedure but also brings transparency in the system by minimizing human involvement.

In the CFMS, cases would not be adjourned till a new date was fixed, which would be determined on a case basis and bench load considerations by gradually taking out the manual element. The built-in scrutiny linked with CRO, FIR, SECP, NADRA, FBR, etc, would reduce the chances of fake and frivolous cases.

Justice Khosa has vowed to utilize modern technology to minimize the chances of adjournments and for the facilitation of the learned counsel.

He said that video links between the Branch Registries of apex court and the Principal Seat would be established through which the learned counsel may address arguments in the courtrooms. Such innovation besides diminishing delays by non-availability of benches at the branch registries also reduces inconvenience and huge expense on the part of all concerned stakeholders.

REDUCING THE BURDEN:

To lessen the unnecessary burden of cases on the courts, the country’s apex judicial policy-making body, National Judicial Committee (NJPMC) has taken several steps to kick out some matters from judicial domain and hand them over to the executive.

NJPMC has decided that the petitions under Sections 22-A and 22-B of the CrPC would not be entertained directly by the courts and the aggrieved persons would have to appear before the superintendent of police (SP) for the purpose.

Sections 22A and 22B of the CrPC, allowed any person to file a petition to the Justice of Peace (a district judge) for registration of an FIR if the relevant police officer declined to register it.

The judicial officers are empowered to hear and order registration of an FIR. They can also order transfer of investigation of a case from one police officer to another.

As the registration of an FIR is purely an administrative issue, petitions filed under sections 22-A and 22-B didn’t only put an extra burden on the district courts but also undermined the autonomy of the police department.

In a similar move,the NJPMC has recommended to empower National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) to issue succession certificate instead of civil courts.

A Succession Certificate is a document that is granted by a civil court to the legal heirs of a deceased who dies without leaving a will. It is mandatory for claiming assets such as bank balance, fixed deposits, shares, mutual fund investments, etc.

This process not only adds to the miseries of deceased person’s family but also overburdens the civil courts. Since NADRA has the family tree of most of the citizens, it would issue the certificates more efficiently and inexpensively.

Justice system is meant to secure the rights of the people and not to snatch them. But for Tariq Mahmood Malik, this system has taken the most beautiful years of his life and kept him away from his family when they needed him the most.

Malik is not alone. The system has become so plagued with the delays and flaws that hundreds people either languish in jails for years or pass away without witnessing the logical conclusion of their case in their lifetime.

To save others from going into the spiral of delayed justice, all the organs of the state need to play their role in rectifying the criminal justice system of the country. If nothing changes, people will lose faith in this system because justice delayed is justice denied.

THE END.